The Robot in the Garden:

Telerobotics and Telepistemology in the Age of the Internet

|

Ken Goldberg, UC Berkeley

Every day the urge grows stronger to get hold of an object at very close range by way of its likeness, its reproduction. --Walter Benjamin, 1936. Many of our most influential technologies: the telescope, telephone, and television, were developed to provide knowledge at a distance. The technology of telerobotics allows scientists to remotely explore distant environments such as the Titanic, Chernobyl, and Mars. Remote control technologies increasingly permeate our daily lives: We have remote controls for the garage door, the car alarm, and the television (the latter a remote for the remote). The Internet makes telerobots available to the public. Webcameras from Mt. Everest to a South African game preserve offer "points of contact between the virtual and the real--spatial anchors in a placeless sea" (Thomas Campanella, Ch. 2). Telerobotic devices go further by providing remote agency, the ability to perform distant actions. (Examples of Internet telerobotic sites are collected at mitpress.mit.edu/telepistemology.) Today, anyone with Internet access can view a distant sunrise, stack blocks in a distant laboratory, or--as the title of this book suggests--tend a distant garden. Access, agency, and authority are central issues for the new subject of telepistemology. As Benjamin's quote anticipates, one of the great promises of the Internet is its potential to increase our access to remote objects. Telerobotic agency provides the ability to physically "get hold of" those objects. The distributed nature of the Internet, designed to ensure reliability by avoiding centralized authority, simultaneously increases its potential for deception. Many Internet cameras and telerobotic systems have been revealed as forgeries, providing unsuspecting users with pre-recorded images masquerading as live footage. The capacity for deception is inherent to the Internet and is most vivid in the context of telerobotics. Are we being deceived? What can we know? What should we rely on as evidence? These are the central questions of epistemology, the philosophical study of knowledge, dating back to Aristotle, Plato, and the ancient Skeptics. The aim of epistemology is to avoid deception and to satisfy the skeptical. Spurred by the inventions of the telescope and microscope in the 17th century, epistemology moved to the center of intellectual discourse for Descartes, Hume, Locke, Berkeley, and Kant. Although epistemology has lost primacy within philosophy, each new invention for communication or measurement raises epistemological questions. This is particularly true of the Internet, which provides widespread access to remote agency without relying on a trusted institutional authority. As the Internet extends our reach, it leaves us increasingly vulnerable to error, deception and forgery. "Now, at the close of the 20th century", Hubert Dreyfus writes in Chapter 3, "new tele-technologies...are resurrecting Descartes' doubts." Telepistemology asks: To what extent can epistemology inform our understanding of telerobotics and to what extent can telerobotics furnish new insights into classical questions about the nature and possibility of knowledge? Artists have always been concerned with how representations provide us with knowledge.1 Telerobotics, like photography and cinema, is a means of representing. As such, it has aesthetic implications; a variety of artworks that incorporate telerobotics have appeared on the Internet. Representations can misrepresent: If Orson Welles' "War of the Worlds" was the defining moment for radio, what will be the defining moment for the Internet? How can artistic strategies be shaped by telerobotics and what is its potential as an artistic medium? New technologies extend and amputate. In The Return of the Real2 (1996), Hal Foster recognizes this bipolar "dis/connection" in the writings of Benjamin3, McLuhan4, Debord5, and Haraway.6

The title of this book refers to the Telegarden, a telerobotic art installation on the Internet where remote users direct a robot to plant and water seeds in a real garden located in the Ars Electronica Museum in Austria: http://telegarden.aec.at. The garden was intended ironically; as a rumination on the Tragedy of the Commons.7 One writer characterized the Telegarden as "planting seeds of doubt."8 My collaborators and I are exploring telepistemological questions about perception, knowledge, and agency in a series Internet art projects. This volume includes 16 original contributions by leading contemporary figures in philosophy, art, history, and engineering, with a postscript by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. In bringing together diverse perspectives on the fundamental philosophical issues surrounding this new technology, we hope to provide a starting point for ongoing discussion. This book focuses on telerobotics (TR) rather than virtual reality (VR). Athough Gibson's term "cyberspace" encompasses both, the distinction is critical: VR is simulacral, TR is distal.9 Michael Benedikt's Cyberspace: First Steps10, published by MIT Press in 1991, initiated a decade of dialogue about the theoretical implications of virtual reality.11 Three years later, the World Wide Web provided the basis for Internet telerobotics, which provoked the present volume. Another book, co-edited with Roland Siegwart and due out in the Fall of 2000, will collect technical papers on twelve specific Internet telerobot projects.12 This book does not attempt to cover the general category of unreliable textual information on the Internet, of which there is no shortage. We focus on the subcategory of information that arises from live interaction with remote physical environments. Accordingly, we do not explicitly address "softbots": information-gathering systems that remain wholly within the confines of software. Nor is this book intended as a treatise on social constructivism, the passionate debate about the fundamental existence of scientific entities such as fields, quarks, and photons. Our focus is less on ontological or metaphysical issues of existence, than on the practical epistemic grounds for knowledge. The two are of course related: A scientific realist firmly believing in the existence of quarks can still be interested in how we know their properties. And the social constructivist, convinced of the constructed nature of the quark model, can nonetheless be interested in what we can know about this model. No one denies the existence of constructed models that are patently false on the Internet: This should not be construed as an argument for social constructivism. The twenty chapters in this book are organized into three overlapping categories: (1) Philosophy, (2) Art, History, and Critical Theory, and (3) Engineering, Interface, and System Design. In the remainder of this Introduction I provide definitions and an overview of the issues raised.

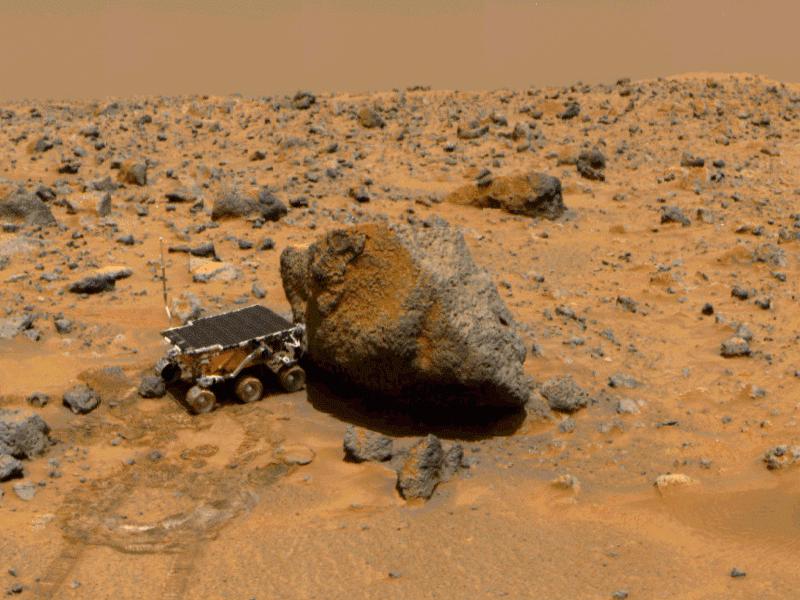

A robot is broadly defined as a mechanism controlled by a computer. A telerobot is a robot that accepts instructions from a distance, generally from a trained human operator. The human operator thus performs live actions in a distant environment and through sensors can gauge the consequences. Telerobotic systems date back to the need for handling radioactive materials in the 1940s, and are now being applied to exploration, bomb disposal, and surgery. In the summer of 1997, the film Titanic opened with undersea telerobots and the NASA's Mars Sojourner telerobot successfully completed a mission on Mars(Figure 1.2). See T. Sheridan's Telerobotics, Automation, and Human Supervisory Control for an excellent review of research issues in telerobotics.13

(Figure 1.3 : Trojan Coffee Pot)

The Internet makes telerobotics accessible to a rapidly growing audience. Text-based Internet interfaces to soda machines were demonstrated in the early 1980s. The first Internet camera was set up by researchers at Cambridge University to monitor the status of a coffee pot (Figure 1.3). In August 1994, my collaborators and I set up the first Internet telerobot. A digital camera and air jet were mounted on a robot arm so that anyone on the Internet could view and excavate for artifacts in a sandbox in our laboratory at the University of Southern California (Figure 1.4).14

In September 1994, Ken Taylor at the University of Western Australia demonstrated a remotely controlled six-axis telerobot on the Internet.15 Also in Fall 1994, Richard Wallace demonstrated a telerobotic camera and Mark Cox put up a system that allows WWW users to remotely schedule photos from a robotic telescope. The early Internet telerobots designed by John Canny and Eric Paulos are described in Ch. 15. Two technical workshops on Internet telerobotics were recently organized: at IROS in Vancouver in November, 1998 and at ICRA in Detroit in May, 1999. Examples of Internet telerobotic projects are available online at http://mitpress.mit.edu/telepistemology.

We begin with a survey of Internet webcameras. Tom Campanella of MIT's Urban Studies and Planning Program describes these as "points of contact between virtual space and real space", and characterizes the distributed ability to set up such cameras as a "grassroots phenomenon" realized by thousands of volunteers. The grassroots metaphor also applies to the subject of many of these cameras: the local landscape. Citing Leo Marx' influential literary analysis16, Campanella characterizes the relationship between the machine and the garden as one of the central dialects in American history. Our ambiguity toward the juxtaposition of robot and garden is compounded by telepistemic concerns that our "live" images may not in fact be live. Campanella suggests that "the most reliable means of checking the veracity of our telepresent landscape may well be the sun itself--the most ancient of our chronographic aids." Philosophy In this section, five authorities consider telerobotics and telepistemology from the perspective of philosophy. Although the role of mediation in technology has been a fixture of philosophy since the 17th century17, the Internet forces a reconsideration. As the public gains access to telerobotic instruments previously restricted to the scientific community, questions of mediation, knowledge, and trust take on new significance for everyday life. Telepistemology, once a theoretical curiosity, becomes a practical problem. As Michael Idinopulos writes in Chapter 17, "skepticism is often treated as a...`philosophical' issue with no real consequences for everyday life....I think this view is deeply and importantly mistaken." We can divide telepistemological issues into two categories: technical and moral. Technical telepistemology is concerned with skeptical questions: Do telerobotics and the Internet really provide us with knowledge? To what extent can they replace ordinary, proximal experience? Moral telepistemology is concerned with ethical questions: How we should act in telerobotically mediated environments? What is the impact of technological mediation on human values? Agency, the ability to perform actions, plays a vital role in telepistemology. Ian Hacking18 gives a superb account of the optical distortions and limitations of early microscopes, noting that perception achieved with a microscope is fundamentally different than perception with the ``naked eye''. Hacking cites G. Berkeley's New Theory of Vision (1710), according to which our sense of vision is acquired not just by passive looking but by intervening in the world. Our ability to actively manipulate a cell as we watch gives us confidence in what we are seeing through the microscope. Agency plays an analogous role in telerobotics which provides embodied perception at a distance. In Chapter 3, Hubert Dreyfus, an authority on Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and the limits of artificial intelligence, notes that Cartesian epistemology arose in response to 17th Century developments in optics and biology. Instruments such as the telescope and the microscope challenged our claims to scientific knowledge and launched a new spirit of doubt and skepticism. Descartes applied this skepticism to human sense organs, treating them as transducers of mediated knowledge whose accuracy was always in question. Dreyfus reviews how philosophers have worked during three hundred years to refute Descartes' mediated conception of the senses--most recently with a phenomenological appeal to embodied perception. As in the 17th Century, we are now experiencing a rapid increase in the extent to which our knowledge is technologically mediated. Dreyfus suggests that advances in Internet telerobotics may reinvigorate the notion that our knowledge of the world is fundamentally indirect. But telerobotics seems unable to reproduce what Merleau-Ponty calls the Urdoxa--a general readiness to cope with objects in the world. Catherine Wilson, author of The Invisible World (1995)19 a historical and philosophical analysis of the microscope, traces our mistrust of instrument-mediated knowledge even further, to the Greek idea that all representations are ignoble. In Chapter 4, Wilson points out that as 18th-century philosophers developed theories of landscape in response to the locomotive, 20th-century phenomenologists developed theories of immediate experience in response to the telephone and radio. These theories privilege everyday objects over the "opaque" and "inscrutable" workings of industrial machines such as hydroelectric plants. Wilson acknowledges that "there are ever fewer gardens...and there are ever more robots," but points out that contemporary technologies such as Internet telerobotics function "not to replace the natural world, but to display it....like windows and telescopes." Although tele-technologies can enhance our respect for and understanding of distant cultures, Wilson cautions that our primitive association of fiction with distance can also lead to violence. In Chapter 5, Albert Borgmann also addresses moral telepistemology although he disagrees with Wilson on several points. Borgmann, author of Information and Reality at the Turn of the Millenium (1999)20, begins by characterizing technical differences between proximal space and mediated space. Borgmann uses the terms "continuity" and "repleteness" to describe the horizontal and vertical dimensions of richness that are lacking in telerobotics. Applying a notion of continuity different than Wilson's, Borgmann claims there is a sharp contrast between the suppleness of natural experience and the brittleness of computer mediated experience. Why then do we increasingly seek out the latter? Borgmann notes that in the age of hunting and gathering, sugars and fats were desirable but rare and scattered, requiring great effort for their collection. When technology made sugars and fats easily and abundandly available, "we retained our desires but lost the tempering circumstances." Borgmann argues that the Internet has played an analogous role with knowledge: Our curiousity remains but we are losing the attentiveness needed to acquire it. Jeff Malpas, author of the 1999 monograph Place and Experience21, argues in Chapter 6 that "mediated knowledge" is a contradiction: Knowledge is inextricably bound up with physical location. He attacks the "Cartesian-Lockean" view of experience, according to which all our knowledge of the world is mediated. It is this view, he argues, which leads to the mistaken idea that technological mediation is a natural extension of ordinary experience. Alvin Goldman's chapter can be read as a response to the skepticism of Dreyfus and Malpas towards telerobotically mediated knowledge. One of the foremost figures in contemporary epistemology,22 Goldman has developed a theory that knowledge can be defined purely in terms of reliable causation. In Chapter 7 he argues that this reliabilist account can be extended to cover telerobotically acquired knowledge. In his view, telerobotic knowledge requires no inference, since reliably caused true beliefs qualify as knowledge. Michael Idinopulos advocates a similar position in Chapter 17. Like Goldman, Idinopulos avoids any commitment to inferences in telerobotic knowledge. But he sees this not as a property of knowledge in general, but as a design feature: By designing telerobotic devices and interfaces that allow users to cope skillfully with distant objects, we can avoid the problematic type of mediation. The result, Idinopulos claims, is knowledge that is causally mediated but epistemically direct. Epistemologists consider our knowledge of propositions, the sorts of things that can be asserted, believed, doubted, and denied, e.g. "The moon is made of cheese." Consider a proposition P. According to Plato's classical definition of knowledge, I know that P if and only if 1) I believe that P, 2) this belief is justified, and 3) P is true. Suppose, for example, that I visit the Telegarden, which claims to allow users to interact with a real garden in Austria by means of a robotic arm. The page explains that by clicking on a "Water" button users can water the garden. Let P be the proposition "I water the distant garden". Suppose that when I click the button, I believe P. Furthermore I have good reason for believing P: A series of images on my computer screen shows me the garden before and after I press the button, revealing an expected pattern of moisture in the soil. And suppose P is true. Thus, according to the definition above, all three conditions are fulfilled and we can say that I know that I watered the distant garden. Plato's tripod of conditions for knowledge are the cornerstone of classical epistemology. Almost forty years ago, epistemologists exposed flaws in the traditional definition. Edmund Gettier showed that not every case of justified true belief should be considered knowledge.23 We can adapt his argument to the case of the telerobotic garden as follows. Let P' be the proposition that I do not water a distant garden. Suppose now that when I click the button, I believe P' and that I have good reasons: An expert engineer informed me about Internet forgeries, how the garden could be an elaborate forgery based on prestored images of a long-dead garden. Now suppose that there is in fact a working Telegarden in Austria but that the water reservoir happens to be empty on the day I click on the water button. So P' is true. But should we say that I know P'? No. But I believe P', I have good reasons, and P' is true. The problem is that even a very good justification is compatible with the falsity of a conclusion that I draw from that justification. Knowledge should not be a matter of luck. Epistemologists developed a variety of Gettier counterexamples that rely on very general features of knowledge and justification. One response, developed by Fred Dretske, is that knowledge should preclude the possibility of error.24 According to Dretske, if I know that P', then it should be impossible for me in the circumstances to be mistaken. Dretske's definition would refute the case where I believe P' (that I do not water the garden), since my justification in this case still leaves me prone to error. Thus according to Dretske I cannot claim to know P'. Perhaps Dretske sets the requirements for knowledge too high; there are very few cases in which we base our beliefs on a justification which precludes the possibility of error. Alvin Goldman offers a more tolerant definition of knowledge. Goldman does not prohibit the possibility of error, but suggests instead that Plato's definition should be refined to stipulate that a belief stand in the right causal relation to the proposition. The phrase "right causal relation" is designed to rule out deviant causal connections. When I use the telerobotic arm to water and observe the distant garden, the fact that I am watering the garden causes me (by way of telephone lines, my modem, etc.) to believe propositions about the garden. This causal chain does not seem to be deviant in any way that would violate Goldman's standards. But as Goldman argues in Chapter 7, a belief does not qualify as knowledge unless the believer can discriminate the actual state of affairs in which the proposition is true from some relevant possible state of affairs in which the proposition is false. This sort of discrimination seems to be precisely what eludes visitors to the Telegarden. A clever programmer can set up a telerobotic forgery cheaply and easily. A number of supposedly telerobotic sites, such as the infamous ToiletCam, have been exposed as forgeries. If forgery illuminates the nature of authenticity; the Internet provides an ample supply of illumination. Art, History, and Critical Theory "Illusion is the first of all pleasures."--Voltaire The word "media" comes from the plural form of Latin for "middle": Mediated experience, in contrast to immediate experience, has something in the middle, between source and viewer. The authors in this section address the aesthetic implications of telerobotic mediation. In Chapter 8, Historian and critical theorist Martin Jay considers the time delay between reality and appearance that is inherent to telerobotic cameras and devices on the Internet. Jay traces the implications of this delay back to the 1676 discovery of the finite speed of light by Danish astronomer Ole Roemer. This "astronomical hindsight" has ontological and epistemological implications ranging from Benjamin's notion of starlight as Memento Mori to Nietzsche's anticipation of a breakdown of the fundamental concept of present grounded in the Aristotelian/Lockean/Berkeleyan/Cartesian notion of atemporal eyesight. Analyzing Baudrillard's reference to the finite speed of light25, Jay argues that that the supposedly "pure simulacra" of virtual reality are in fact parasitic on prior corporeal experience and that a telerobotic image on the Internet, although delayed, retains the attenuated indexical trace of its distant source. Lev Manovich, artist and new media critic, begins Chapter 9 by analyzing how the index is subverted in cinema. The ability to record and edit images into spatial and temporal montage allows film to "overcome its indexical nature, presenting a viewer with scenes that never existed in reality". Cinema does not rely on the viewer's suspension of disbelief; one of our most successful industries has been built on the engineering of illusion26. Some films, such as Blow Up, Capricorn One, The Truman Show, and The Matrix, incorporate this process into their subject matter. Although sports is an area where live broadcasts are highly valued and any form of deception is prosecuted, the recent success of professional wrestling on television suggests that sports viewers may be developing an increased appetite for irony. Manovich considers virtual reality as the culmination of a trend toward deception that goes back to Potemkin's 18th Century construction of false facades in Czarist Russia. He describes teleaction, the ability to act over distances in real time, as a "much more radical technology than virtual reality." Citing Bruno Latour's definition of power as "the ability to mobilize and manipulate resources across space and time," Manovich notes that telerobotic systems not only represent reality but allow us to act on it. Now that Internet telerobotic systems deliver teleaction to a broad audience, it is vital to reconsider the relationship between objects and their signs. Television allowed objects to be transformed instantly into signs; telerobotics allows us, through signs, to instantly touch the objects they represent. The boundaries between what is seen and what is staged are increasingly blurry....the crucial issue may not be camera but a gnawing sense that the world itself, knowable only through imprecise perceptions, is a tissue of uncertainties, ambiguities, fictions masquerading as facts and facts as tenuous as clouds. –V. Goldberg27 Artists were among the first to use telerobotics to explore this "gnawing sense" of uncertainty. There is a rich history of Communications Art from Moholy-Nagy to Nam Jun Paik, Roy Ascott, and Douglas Davis. Much of this "telematic" artwork was based on telephone and satellite technology; contemporary artists are now incorporating telerobotics into their work. An (incomplete) list includes: Maurice Benayoun, Shawn Brixey, Susan Collins, Elizabeth Diller, Ken Feingold, Scott Fisher, Masaki Fujihata, Kit Galloway, Greg Garvey, Emily Hartzell, Lynn Hershman, Perry Hobermann, Eduardo Kac, Knowbotic Research, Rafael Lozano-Hammer, Steve Mann, Michael Naimark, Mark Pauline, Eric Paulos, Simon Penny, Sherry Rabinowitz, Michael Rodemer, Julia Scher, Ricardo Scofidio, Paul Sermon, Joel Slayton, Nina Sobell, Stelarc, Gerfried Stoker, Survival Research Laboratories, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Victoria Vesna, Richard Wallace, Norman White, and Steve Wilson. Why there is any aesthetic difference between a deceptive forgery and an original work challenges a basic premise on which the very functions of collector, museum, and art historian depend. --Nelson Goodman28 Hunt29 and Pescovitz30 review recent trends in telerobotic art. One recent example is Refresh, a Internet-based art installation by Diller and Scofidio.31 This project juxtaposes a live webcamera with 11 videos staged by professional actors. Each image is accompanied with a fictional narrative such that it is impossible to tell which is the live webcamera.32 Brazilian-born artist Eduardo Kac has exhibited projects involving telerobotics since 1986. His "dialogical" strategy creates a dynamic interplay between presence and absence, where telepresentation is contrasted with representation. In Chapter 10, Kac describes four of his art projects, including Rara Avis, a critique of exoticism where a telerobotic wooden bird was placed into a cage with 30 zebra finches. Visitors on the Internet access cameras inside the avatar's head to achieve the rare bird's eye view from inside the cage. In his Uirapuru project,real-time video was inserted into a false Internet interface, forcing bird and human participants to navigate through a complex network of true and fictitious projections. Kac's Telepresence Garment placed the artist into a sealed rubber bag where his movements and voice were contained and controlled by an external human "master" transmitting instructions from an art gallery. For Kac, telepresence art suggests a new ecology of carbon and silicon that modulates our "very notion of reality." In Chapter 11, new media art curator and critic Machiko Kusahara reviews the work of five artists who use telerobotics. By allowing users to affect the real world by means of actions at a distance, these artists create a tension between "here and there". Some, such as Lynn Hershman Neeson use this dichotomy to simultaneously represent multiple points of view, so that the user is at once both the observer and the observed. Others such as Masaki Fujihata use telerobotics to establish a sense of human community and cooperation despite physical separation. Others emphasis its limitations,how telerobotics leads to alienation in the case of Ken Feingold, and in Stelarc's Internet performances, a potential for inflicting physical pain. Artist and critic Marina Grzinic considers the aesthetic implications of time-delay in Chapter 12. Often seen as an aggravating and problematic aspect of Internet telerobotics, Grzinic defends time-delay as a potential resource for representing space and time. As Walter Benjamin suggested in the context of photography, shortening the "exposure time" can drain the essence from an image. Citing Baudrillard33, Grzinic notes the absence of aura in the sterile television images of recent bombings in Iraq and Serbia. Because telerobotic images are delayed, they remind us of the spatial and temporal relations separating us from the subjects of the images. Time-delay thus emerges as an aesthetic and telepistemological asset, leading to a deeper view of imaging technology and the world it seeks to capture. In Chapter 13, art historian Oliver Grau considers how a Gnostic desire to transcend the limitations of the physical body provides an early referent for contemporary interest in telerobotics. Grau focuses on telepresence--the superclass of immersive technologies that often make use of helmets, goggles, and 3-D projections.34 Grau sees the realist illusions of renaissance art and the panaromas of the 19th century as early examples of telepresence technology. Robots and their precursors, golems, puppets, and androids, provide a different strategy for transcending the body. Grau discusses how Simon Penny's newest art project combines these themes of bodily rejection, illusion, and automata. Grau concludes with the 20th Century writing of Ernst Cassirer and Paul Valéry on the relationship between distance and aesthetic contemplation. Engineering, Interface, and System Design The third section provides perspectives from engineers and designers. Blake Hannaford, an authority on telerobotics, provides a historical overview of telerobotics research in Chapter 14. Focusing on the issues of time delay, control, and stability, Hannaford reviews work of Goertz in the 1950's who developed mechanical teleoperators to handle radioactive materials at Los Alamos. As mechanical linkages were replaced by electrical signals, kinematics and dynamics were incorporated into efficient computer control algorithms for telerobotic systems. When control is attempted over long distances, for example on the Internet, variable time delays introduce the potential for system instabilities. Hannaford reviews several of the techniques proposed to compensate, such as Sheridan's Supervisory Control, and Conway and Volz' Time Clutch. The distortions inherent to telerobotics pose fundamental questions of telepistemology which are compounded on the Internet, where the user may not know or trust the engineers who designed the system. In Chapter 15, Computer Scientists Canny and Paulos address computer-mediated communication from Cartesian and phenomenological perspectives. The current Cartesian model for teleconferencing ignores the role of the body and breaks communication into separate channels for video, text, and audio. The results are often stilted and unsatisfying. Canny and Paulos propose an alternative model based on a phenomenological integration of physical cues and natural responses. Canny and Paulos have designed a range of "tele-embodiment" devices: helium-filled blimps to ground-based telerobots, to facilitate believable interactions over the Internet. As issues of trust and intimacy arise in their experiments, Canny and Paulos conjecture that future telepresence systems will be "anti-robotic". Rather than automatons blindly repeating orders, "social machines" and toys of the future will express a wide range of behaviors including emotions. Telepistemology may help us to better understand not only what can be conveyed online, but also what is essential to hugs and handshakes. In Chapter 16, Judith Donath, director of the MIT Media Lab's Sociable Media Group, addresses skepticism in our knowledge of other minds. This question has long been of interest to philosophy (the problem of other minds) and cognitive science (the Turing Test, Joseph Weizenbaum's ELIZA and now Internet "chatterbots" such as Richard Wallace's ALICE.35 As Canny and Paulos point out, technology that mediates our interaction with other people--chat rooms, email, video conferencing, etc.--can severely restrict the range of social cues that guide our behavior towards them. Our ability to recognize online deception has important implications. Unless we know who we are communicating with, we do not know how to behave. Consistent with Wilson's point in Chapter 4, Donath suggests that as telerobotics enables remote agency, it may invite us to inflict harm on those whose identity, and even humanity, remains hidden from view. In Chapter 17, Michael Idinopulos uses telepistemological considerations to draw normative conclusions about telerobotic interface design on the Internet. Drawing on Descartes, Berkeley, and contemporary philosopher Donald Davidson and Richard Rorty, he distinguishes between "causal" and "epistemic" mediation: Knowledge is always mediated causally (by the events that produce it), but it is mediated epistemically only if it is the product of inference. Skepticism--the central problem in epistemology--challenges knowledge that is epistemically mediated. If knowledge from a distance is the goal of telerobotic devices, then epistemic immediacy should be the goal of interface design. This is achieved by interfaces that allow the user to "cope skillfully" in the remote environment--to interact instinctively and unreflectively with distant objects, rather than treating them as theoretical entities to be inferred from evidence on a video screen.36 Like eyeglasses, telescopes, and microscopes, telerobotic devices should mediate our knowledge causally, but not epistemically. When we visit a telerobotic web site, we should not see the interface itself. We should see through the interface to the distant environment beyond. As a postscript, Merleau-Ponty's 1945 essay, The Film and the New Psychology37 provides a precedent for philosophy's role in media technology. Merleau-Ponty begins by describing how both Gestalt psychology and phenomenology reject the Cartesian dichotomy between mind and body. Rather than analyzing each sensation separately, the new approach recognizes that we as humans respond as "beings thrown into the world and attached to it by a natural bond." Merleau-Ponty applies this model of perception to the aesthetics of cinema. For example, Pudovkin's sequences using the face of Mosjoukin are now familiar examples of temporal Gestalt. Merleau-Ponty's essay elegantly illustrates how "modes of thought correspond to technical methods" and recalls Kant's remark that in knowledge, imagination serves the understanding, whereas in art, understanding serves the imagination. Finally, does it matter whether a telerobotic site is real or not? Perhaps not to the majority of casual net surfers, but to those who spend enough time to care, to patiently interact with a purported telerobotic site, discovering the site to be a forgery can be as traumatic as the discovery by a museum curator of a forgery among one of the Rembrandts in the permanent collection.

Notes

1 L. Shlain, Art and Physics: Parallel Visions in Space, Time, and Light, Quill Press, 1991, and The Alphabet v. The Goddess: The Conflict Between World and Image, Viking Press, 1998. 2 H. Foster, The Return of the Real, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1996, 3 W. Benjamin, Illuminations, Harry Zohn, transl., Shocken Books, New York, 1969. 4 M. McLuhan, Understanding Media, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1964. 5 G. Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, Zone Books, 1969. 6 D. Haraway, "A Manifesto for Cyborgs," Socialist Review 80, 1995. 7 G. Hardin, "The Tragedy of the Commons," Science 162: 1243-1248, 1968; P. Lenenfeld, "Technofornia," Flash Art, 1996; W. Mitchell, "Replacing Place" in P. Lunenfeld, ed. The Digital Dialectic, MIT Press, 1999. 8 R. Winters, "Planting Seeds of Doubt," Time Digital, 8 March 1999. 9 K. Goldberg, "Virtual Reality in the Age of Telepresence" Convergence 4 (1): 33-37, March 1998. 10 M. Benedikt, Cyberspace: First Steps, MIT Press, 1991. 11 P. Levy, Becoming Virtual: Reality in the Digital Age, Plenum Press, 1998; M. Heim, Virtual Realism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997; M. Poster, "Theorizing Virtual Reality: Baudrillard and Derrida" in Maire-Laure Ryan, ed., Cyberspace Textuality, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1999; J. Steuer, "Defining Virtual Reality: Dimensions Determining Telepresence," F. Biocca and M. R. Levey, eds., Communication in the Age of Virtual Reality, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 33-56. See also Feenberg and Hannay, eds., Technology and the Politics of Knowledge, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1995. For edited collections of critical theory on new media, see: L. Hershman,ed., Clicking In, Bay Press, 1996; Kroker and Kroker, eds., Digital Delirium, St. Martin's Press, 1997; Sommerer and Mignonneau, eds., Art @ Science, Springer Verlag, 1998; and the very recent P. Lunenfeld, ed., The Digital Dialectic, MIT Press, 1999. 12 Examples include: G. Bekey, Y. Akatsuka, and S. Goldberg, 1998, "Digimuse: An Interactive Telerobotic System for Viewing of three-dimensional art objects" IROS 1998; P. Saucy and F. Mondada, "Khep-on-the-web: One year of access to a mobile tobot on the Internet" IROS 1998; R. Simmons, "Xavier: An Autonomous Mobile Robot on the Web"; Taylor and Dalton, "A Framework for Internet Robotics" IROS 1998; Siegwart, Wannaz, Garcia, and Blank, "Guiding Mobile Robots Through the Web",all included in Workshop on Web Robots, IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Robots and Systems (IROS), organized by Roland Siegwart, 1998. 13 T. Sheridan, Telerobotics, Automation, and Human Supervisory Control, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1992. See also Sheridan's "Musings on Telepresence and Virtual Presence" Presence Journal 1:1, 1992. 14 K. Goldberg, M. Mascha, S. Gentner, J. Rossman, N. Rothenberg, C. Sutter and J. Wiegley, "Beyond the Web: Manipulating the Real World" Computer Networks and ISDN Systems Journal, 28(1), December 1995 and K. Goldberg, S. Gentner, C. Sutter, and J. Wiegley, "The Mercury Project: A Feasibility Study for Internet Robots", IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine (forthcoming, 1999); 15 B. Dalton and K. Taylor, "A Framework for Internet Robotics" IROS 1998 16 L. Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1964. 17 R. Descartes, Meditations (1641) translated in Cottingham, John, ed., Meditations on First Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1996. 18 I. Hacking, Representing and Intervening, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1983. 19 C. Wilson, The Invisible World, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1995. 20 A. Borgmann, Information and Reality at the Turn of the Millenium, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999. 21 J. Malpas, Place and Experience, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999. 22 A. Goldman, Epistemology and Cognition, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1986; and A. Goldman, Knowledge in a Social World, Clarenden Press, Oxford, 1999. 23 E. Gettier, "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?" Analysis 23: 121-3. 24 F. Dretske, "Conclusive Reasons," Australasian Journal of Philosophy 49: 1-22. 25 J. Baudrillard, "Fatal Strategies" in Selected Writings, ed. Mark Poster, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1988. 26 For an in-depth discussion of phenomenology in film, see V. Sobchack, The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1992. 27 V. Goldberg, Review of Jeff Wall Photography, New York Times, 16 March 1997. 28 N. Goodman, "Art and Authenticity" in Languages of Art, Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1968. 29 D. Hunt, "Telepresence Art," Camerawork Journal, 1999. 30 D. Pescovitz, "Be There Now: Telepresence Art Online," Flash Art 32 (205), pp. 51-52. 31 www.diacenter.org 32 In Paris, the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art hosted a major exhibition involving Internet telecameras from June 29-November 30 1999. See www.fondation.cartier.fr. 33 J. Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, transl. Paul Patton, Power Publications, Sydney. 34 M. Minsky, "Telepresence" Omni 2 (9), p. 48. Also see J. Steuer, "Defining Virtual Reality: Dimensions Determining Telepresence" in F. Biocca and M. R. Levy, eds., Communication in the Age of Virtual Reality, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, New Jersey, 1995, pp. 33-56. Immersive telepresence is not yet feasible on the Internet due to transmission delays. See also T. Campanella's discussion of telepresence in Chapter 2 of this volume. 35 R. Wallace designed Alice, a sophisticated Internet chatterbot: www.alicebot.org. 36 H. Dreyfus and S. Dreyfus, Mind Over Machine : The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer, Free Press, New York, 1986. 37 M. Merleau-Ponty, The Film and the New Psychology. The 1945 essay from Sense and Non-Sense, transl. H. Dreyfus and P. Dreyfus, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois, 1964.

For more information please contact Prof. Goldberg at goldberg@ieor.berkeley.edu, or 510-643-9565. This text can be found online at:

|